Download Asset Allocation | January 2025

It’s Been a Long December

Economic Update

Uncertainty around policy and slowing growth

By Regions Economic Division

The tradition of celebrating the New Year is older than Western civilization. Nearly 4,000 years ago, the Babylonians celebrated the end of one year and the birth of the next. Much has changed since then, but the spirit of renewal and optimism endures. As the Counting Crows sang in A Long December, “Maybe this year will be better than the last.” With changes in the air under a new administration, this is a sentiment shared by many. However, the hope for a better future does not always become a reality, especially when markets have been quite generous to investors since the end of 2022. Since then, the S&P 500 has had a run for the record books. Only about one quarter of calendar years in S&P 500 history have been better than 2024, and in nearly a century, just six two-year calendar periods have been better. The ever-dominant “Magnificent 7” stocks continue to cast a growing shadow of doubt among even the most ardent Graham and Dodd disciples that equity market multiples could soon begin a reversion to the mean. Enthusiasm around shifting political winds and a resounding faith in American exceptionalism seem to drown out concerns around a resurgence in inflation and interest rates. Will this year truly be better than the last? Or will missteps on immigration and trade policy give the mean reversionists their long-awaited vindication? As the year unfolds, investors can only hope that enthusiasm around equity markets and economic strength does not fade and falter like so many New Year’s resolutions when the path forward becomes rougher road than previously envisioned.

Economists as a group are generally smart and knowledgeable people. However, when it comes to making a detailed forecast of the path of the U.S. economy in 2025, even our own economist, Richard Moody, has been quoted as saying “No one really knows anything.” After all, even if the broad contours of changes in fiscal, regulatory, trade, and immigration policy to be seen over coming months are taking shape, the range of potential outcomes around the specific details in each of those areas is so wide that it is hard to have much, if any, confidence in any specific 2025 forecasts before those details emerge. As this is January, we are bound, we’re pretty sure by law, to offer an outlook for the economy in the year ahead. Our January 2025 baseline forecast, however, may be better seen as a point of reference as to how we’ll see the impacts of policy changes as the details of those changes emerge in the months ahead.

As in 2023, real GDP growth surprised to the upside in 2024, and for the same reasons. The combination of rapid growth in the supply of and productivity of labor allowed for above-trend real GDP growth while allowing for further deceleration in inflation, though progress on that front stalled as 2024 came to a close. Although the Q4 data are not yet available, full-year 2024 real GDP growth was tracking at 2.8%, handily beating our forecast of 2.1% growth, and even further outpacing the blue chip consensus forecast of 1.6% growth. We do not, however, expect another year of above-trend growth in 2025; our baseline forecast anticipates real GDP growth of 2.2% in 2025, with a marked slowdown in labor supply growth and a “higher for longer” interest rate profile weighing on growth.

While the pace of job growth slowed as anticipated in 2024, the labor force grew faster than we anticipated, putting upward pressure on the unemployment rate. For full-year 2024, the unemployment rate averaged 4.0%, just above our forecast of 3.9%. While we expect job growth to slow further in 2025, we expect slower labor supply growth to offset much of the upward pressure on the unemployment rate, which we expect to average 4.1% for full-year 2025. Despite slowing job growth, aggregate labor earnings – the largest block of personal income – continue to grow at a rate faster than inflation, which has been a support for consumer spending. We expect growth in consumer spending to realign with growth in after-tax income in 2025, after what has been a wide gap over the past few years.

While we expected headline and core inflation as measured by the PCE Deflator to remain above the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) 2.0% target through 2024, we also expected a more pronounced slowdown than proved to be the case, as inflation began to reaccelerate over the final months of 2024. Our January baseline forecast has both headline and core PCE inflation averaging 2.4% for full-year 2025. Although not precluding further cuts in the Fed funds rate, particularly with many FOMC members nervously eyeing softer labor market conditions, that inflation is proving to be so persistent does limit the scope for further funds rate cuts. After 100 basis points of cuts in 2024, as anticipated, we anticipate two 25-basis-point cuts in 2025. Even should that prove to be the case, it may bring little relief from elevated long-term interest rates, as concerns over persistent inflation and the growing federal government budget deficits may put a floor under yields on longer-term U.S. Treasuries. To the extent that mortgage rates are influenced by 10-year U.S. Treasuries, this does not bode well for the housing market, and we expect starts and sales of new single-family homes to be lower than in 2024.

As we discussed last month, potential changes to immigration and trade policy are sources of uncertainty around the 2025 outlook. We think it important to note that after December’s edition, the U.S. Census Bureau released their latest estimates of U.S. population. The updated data incorporate revised methodology for estimating international migration, which we and others have argued Census was significantly undercounting over recent years. Indeed, the latest estimates show far greater U.S. migration growth since 2022 than had previously been estimated, which the Census data now show to have accounted for roughly 85% of total U.S. population growth from 2022 through 2024. This highlights the extent to which foreign- born labor has been the catalyst for the faster growth in the supply of labor over this span, but also highlights the potential for there to be an adverse labor supply shock – resulting in growth being lower and inflation being higher than our baseline forecast anticipates – should there be a significant slowdown in the inflow of foreign- born labor. By year-end 2024, there were already signs of such a slowdown, and this is clearly something to monitor in months ahead. As we see it, the potential effects on wages, output, and inflation stemming from changes to immigration policy would be felt much more acutely, and more immediately, than the effects of expanded tariffs.

In terms of consumer spending, there is a clear divide across income/wealth lines. Many lower-to-middle-income households are far less likely to have reaped the benefits of rising asset prices in recent years and have curtailed discretionary spending, while higher-income households and those with significant increases in net worth continue to engage in such spending. A sharp correction in equity prices and/or a meaningful decline in house prices, however, could easily trigger negative wealth effects that would curb discretionary spending. To the extent interest rates remain elevated, spending on durable goods will be impaired while households with variable-rate debt obligations, including credit card debt, will get little, if any, relief from debt service burdens. These factors all pose downside risks to our forecast for growth in 2025.

Although the U.S. economy ended 2024 on firm footing, there is considerable uncertainty looming over the outlook for the year ahead. Therefore, it seems fitting to wrap our 2025 outlook by repeating a call we clearly got right in both our 2023 and 2024 outlooks, which is that at the end of the year, the economy is unlikely to look as we, at the start of the year, expect it to, even if we do not now know why that will be the case.

Investment Strategy Update

Regions Multi-Asset Solutions & Highland Associates

We reserve healthy skepticism after back-to-back +25% gains amid lofty valuations, but it seems premature to turn bearish on domestic stocks. Especially considering the prospect of double-digit earnings growth for 2025, the secular AI theme, and likelihood that the U.S. economy is set to receive a booster shot of pro-business policies out of Washington, D.C., supporting U.S. companies. While we don’t expect another year of 20%-plus gains for U.S. large-cap stocks given lofty starting valuations, valuation is a poor timing tool and indicator. Catalysts rather than valuation are better predictors of near-term market reversals, and strong secular drivers like AI have a history of propelling stocks for longer with valuations well above what most market participants believed possible.

Much has been made of the current market backdrop sharing similarities with the 1996 through 1999 time frame. Most notably, both environments either were or have been characterized by powerful tailwinds for secular growth stocks, as the dawn of the internet kicked off the late-1990’s rally, and the onset of the artificial intelligence (AI) revolution has acted as a catalyst for upside in recent years. From a performance perspective, the S&P 500 generated an annualized total return of more than 26% from 1996 through 1999 as the index strung together four consecutive calendar years in which it generated a total return north of 20%. While this is not our expectation for U.S. large-cap stocks in coming years, given valuations, it is worth noting the possibility that it would not be without historical precedent.

This leaves us open to the possibility that returns could surprise to the upside in the coming year, but our base case calls for the S&P 500 to rise in line with year-over- year earnings growth as policy uncertainty contributes to elevated volatility and a choppier backdrop for stocks along the way. Investors could spend much of the first half of this year recalibrating their expectations for economic growth, inflation, and the outlook for monetary policy due largely to policy shifts out of Washington, D.C. It’s also worth noting that, on average, the first quarter of a U.S. President’s term has generated the lowest S&P 500 return of any quarter in the four-year presidential cycle. Markets crave the certainty that often comes from gridlock in our nation’s capital amid divided government, as this dynamic ensures that little in the way of sweeping policy changes are enacted. With a single party set to control the White House, House of Representatives, and the Senate in the coming year(s), impactful and abrupt policy changes could result in equity price volatility – both to the upside and downside – remaining elevated relative to recent years as a result.

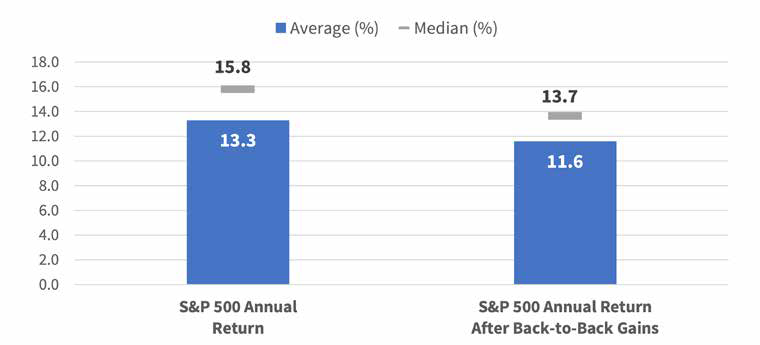

Since 1975, Average Annual S&P 500 Return Lower Than Normal After Back-to-Back Annual Gains

Source: Bloomberg

Small- and mid-cap U.S. stocks are likely to benefit as the M&A outlook improves, but near-term rate headwinds remain. The last quarter was a winding road to nowhere for small- and mid-cap stocks as the S&P 1000 SMID index returned an unremarkable 0.1%. Despite posting a 9.5% return in November, the index gave back the bulk of those gains in December. That drawdown was exacerbated by the FOMC meeting, as the near-term inflation forecast signaled a near-term pause and shallower trajectory for rate cuts. Futures are now pricing in just 25 basis points of cuts in 2025, down from 75 at the start of December. This has been a setback for cyclical sectors, particularly those further down the market cap spectrum. However, earnings expectations have flattened out, one early sign that small- and mid-caps could be close to finding a near-term bottom.

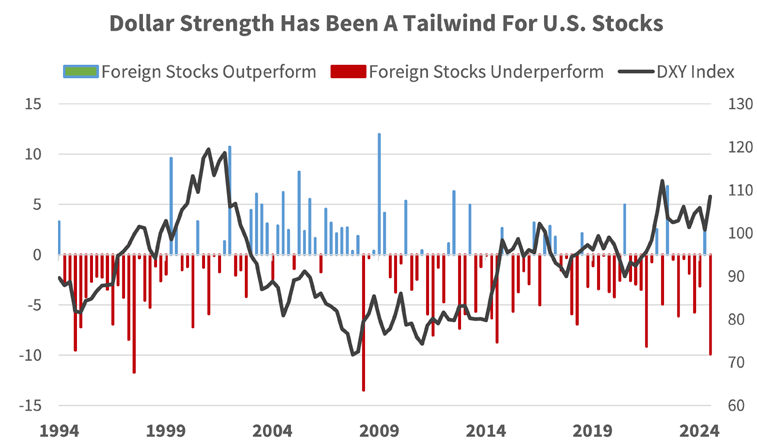

Even though U.S. equities maintain the growth advantage, low expectations in international companies could be a setup to “under promise” and “over deliver” on return expectations. The MSCI EAFE index and MSCI EM index fell by 8.3% and 8.1%, respectively, in the fourth quarter of 2024, with most of those losses coming from currency effects. There appears to be room for mean reversion and a modest drop in the U.S. dollar given the magnitude and speed of the recent run-up, much of which appears centered on uncertainty surrounding immigration and trade policies. We enter the new year comfortable with our international holdings as a play on mean reversion and potential dollar depreciation, but this scenario would likely present opportunities to rebalance back into U.S. equities.

Some stability or weakness in the U.S. dollar would be welcomed by foreign stocks. The U.S. dollar’s ascent throughout the fourth quarter and into the new year has put significant strain on international equities. To begin the year, the U.S. Dollar Index (DXY) has traded in the 109/110 range for the first time since late 2022, leading market participants to question how much stronger the greenback can get or if too much good news is already priced into it. A rapidly appreciating dollar will be a headache for the President at some point as it lowers demand for U.S. goods from abroad, so announced policy changes could look quite different when implemented based on earlier market reactions to them. International developed and emerging market stocks could get a reprieve if the U.S. dollar has discounted policy shifts that either don’t materialize or are watered down relative to expectations. The case could be made that U.S. exceptionalism providing a boost to U.S. stocks relative to the rest of the world could still be in early innings, which could imply persistent dollar strength in the coming years.

The “Trump Bump” Failed to Buoy SMID for Long Last Time

Source: Bloomberg

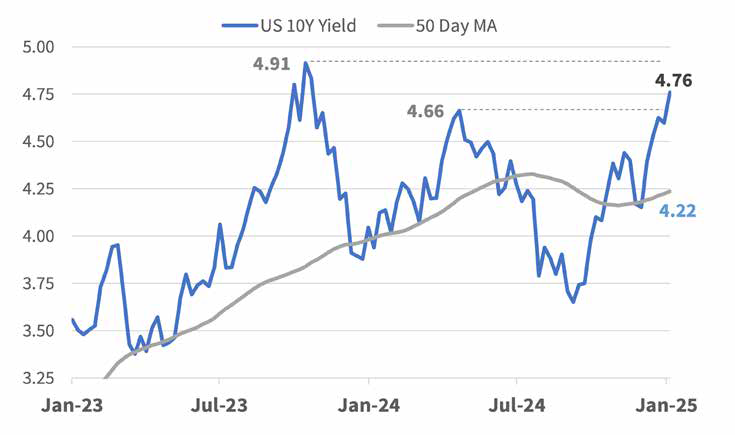

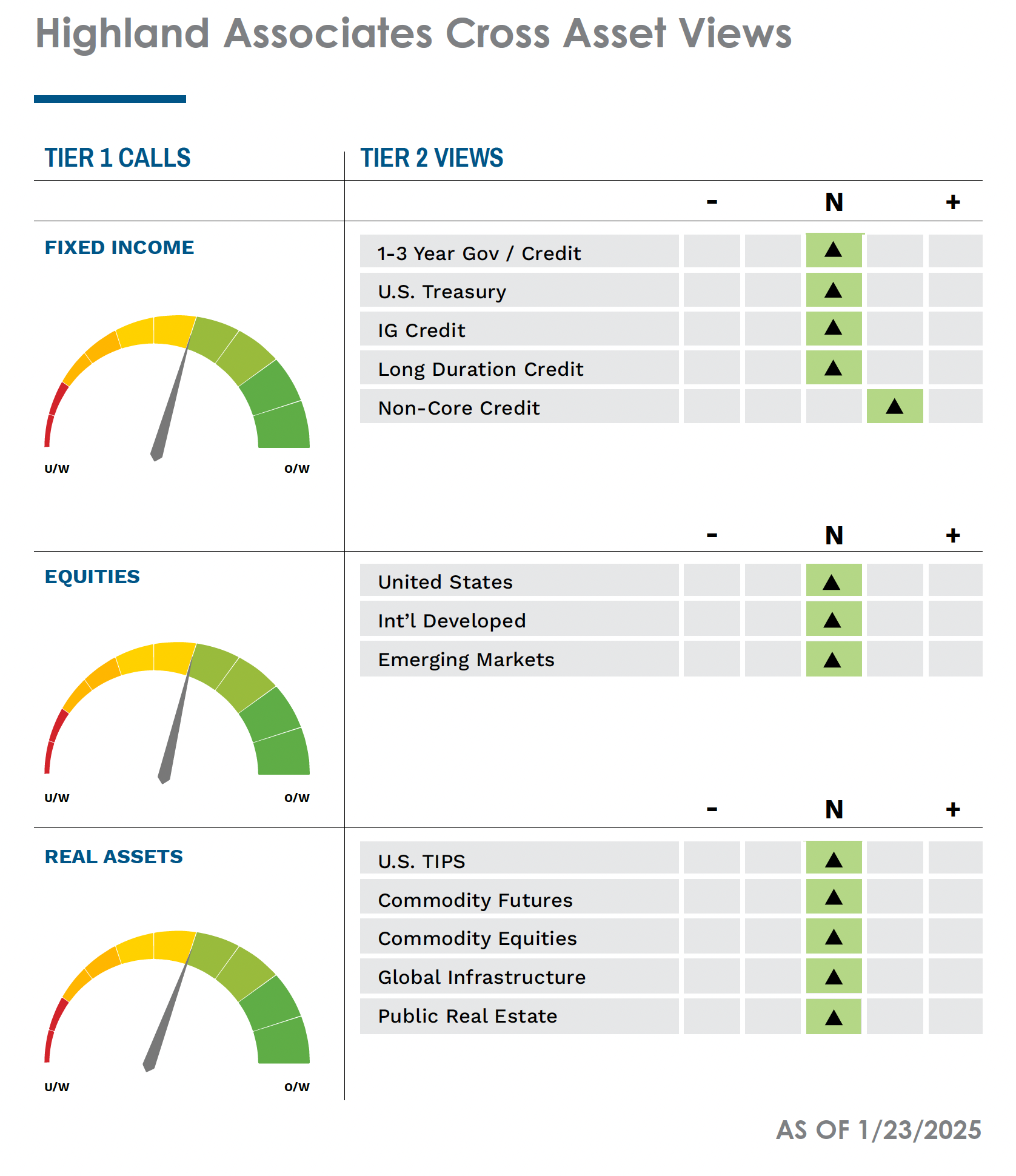

Bonds continue to be a valuable diversifier, as interest rate volatility is likely to persist. The 10-year Treasury yield continued to rise in early January as trade/tariff rhetoric, U.S. deficit and spending rose, and additional signs of sticky inflation joined forces to put downward pressure on prices of higher- quality, longer-duration bonds. We believe the 10-year U.S. Treasury, specifically, is in the process of carving out a new trading range with a floor of support likely in the 4.40%/4.45% area, but with the upper end of the new range still to be determined at the start of the year. At the time of this writing, the 10-year yield hovered around 4.75%, a level that provided resistance in April of 2024 and ultimately proved to be the high for the year. However, that was before immigration and trade uncertainty, as well as concerns surrounding the U.S. government’s budget deficit, entered the equation for investors. So, a break above that level and potential test of the 5% level could be in the cards sometime this year.

After the backup in yields, long-dated Treasuries now more appropriately or adequately compensate investors for taking interest rate risk. However, investors still face a dilemma regarding when and to what degree to extend portfolio duration given a lack of clarity surrounding immigration, trade policies, and, in turn, inflation. With the 10-year yield running into last year’s resistance, we would expect some to lock in these higher yields for longer by shifting capital further out on the Treasury curve.

Higher Trading Range for the U.S. 10-Yr. Likely

Source: Bloomberg

In this environment, diversification across maturity buckets, segments of the fixed-income market, and geographies could be rewarded, as attempting to call a top in yields is ill advised. Treasuries, both short and longer-dated issues, can play a valuable role, as can exposure to asset- and mortgage-backed securities along with investment-grade and high-yield corporate bonds, all of which should perform relatively well assuming the U.S. economy remains resilient. Abroad, for the first time in at least a half-decade, we are looking at opportunities to increase exposure to developed market sovereign bonds as total return on a currency-hedged basis appears attractive against domestic yields.

Credit risk is still preferable to interest rate risk for now. Credit spreads on high-yield corporates widened in December as portfolio rebalancing pulled capital from riskier segments of fixed income that outperformed in 2024. However, high- yield corporate bonds have fared well on both an absolute and relative basis to kick off the new year, recovering approximately half of what they lost in December as investors jumped at the chance to clip a 7.5% coupon after a pre- Christmas pullback. The shorter-duration profile of the High Yield Index has also provided a tailwind for the asset class as investors’ uncertainty about interest rates remains.

In December, the economic score shifted to “risk-on,” bringing the HDI total score to 100%. The last two times the risk score was this high were February of 2021 and June of 2019. The yield curve also fully normalized in December, with all segments of the curve sloping upward to end the year. Overall, the index suggests risk-on positioning, but given our expectation for heightened volatility early in a new presidential regime, better entry points are likely to present themselves later in the year to take incremental risk.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES: This publication has been prepared by the staff of Highland Associates, Inc. for distribution to, among others, Highland Associates, Inc. clients. Highland Associates is registered with the United States Security and Exchange Commission under the Investment Advisors Act of 1940. Highland Associates is a wholly owned subsidiary of Regions Bank, which in turn is a wholly owned subsidiary of Regions Financial Corporation. Research services are provided through Multi-Asset Solutions, a department of the Regions Asset Management business group within Regions Bank. The information and material contained herein is provided solely for general information purposes only. To the extent these materials reference Regions Bank data, such materials are not intended to be reflective or indicative of, and should not be relied upon as, the results of operations, financial conditions or performance of Regions Bank. Unless otherwise specifically stated, any views, opinions, analyses, estimates and strategies, as the case may be (“views”), expressed in this content are those of the respective authors and speakers named in those pieces and may differ from those of Regions Bank and/or other Regions Bank employees and affiliates. Views and estimates constitute our judgment as of the date of these materials, are often based on current market conditions, and are subject to change without notice. Any examples used are generic, hypothetical and for illustration purposes only. Any prices/quotes/statistics included have been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but Highland Associates, Inc. does not warrant their completeness or accuracy. This information in no way constitutes research and should not be treated as such. The views expressed herein should not be construed as individual investment advice for any particular person or entity and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments, strategies or banking services for a particular person or entity. The names and marks of other companies or their services or products may be the trademarks of their owners and are used only to identify such companies or their services or products and not to indicate endorsement, sponsorship, or ownership by Regions or Highland Associates. Employees of Highland Associates, Inc., may have positions in securities or their derivatives that may be mentioned in this report. Additionally, Highland’s clients and companies affiliated with Highland Associates may hold positions in the mentioned companies in their portfolios or strategies. This material does not constitute an offer or an invitation by or on behalf of Highland Associates to any person or entity to buy or sell any security or financial instrument or engage in any banking service. Nothing in these materials constitutes investment, legal, accounting or tax advice. Non-deposit products including investments, securities, mutual funds, insurance products, crypto assets and annuities: Are Not FDIC-Insured I Are Not a Deposit I May Go Down in Value I Are Not Bank Guaranteed I Are Not Insured by Any Federal Government Agency I Are Not a Condition of Any Banking Activity.

Neither Regions Bank nor Regions Asset Management (collectively, “Regions”) are registered municipal advisors nor provide advice to municipal entities or obligated persons with respect to municipal financial products or the issuance of municipal securities (including regarding the structure, timing, terms and similar matters concerning municipal financial products or municipal securities issuances) or engage in the solicitation of municipal entities or obligated persons for such services. With respect to this presentation and any other information, materials or communications provided by Regions, (a) Regions is not recommending an action to any municipal entity or obligated person, (b) Regions is not acting as an advisor to any municipal entity or obligated person and does not owe a fiduciary duty pursuant to Section 15B of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 to any municipal entity or obligated person with respect to such presentation, information, materials or communications, (c) Regions is acting for its own interests, and (d) you should discuss this presentation and any such other information, materials or communications with any and all internal and external advisors and experts that you deem appropriate before acting on this presentation or any such other information, materials or communications.

Source: Bloomberg Index Services Limited. BLOOMBERG® is a trademark and service mark of Bloomberg Finance L.P. and its affiliates (collectively “Bloomberg”). BARCLAYS® is a trademark and service mark of Barclays Bank Plc (collectively with its affiliates, “Barclays”), used under license. Bloomberg or Bloomberg’s licensors, including Barclays, own all proprietary rights in the Bloomberg Barclays Indices. Neither Bloomberg nor Barclays approves or endorses this material or guarantees the accuracy or completeness of any information herein, or makes any warranty, express or implied, as to the results to be obtained therefrom and, to the maximum extent allowed by law, neither shall have any liability or responsibility for injury or damages arising in connection therewith.