Download Asset Allocation | December 2024

Santa Claus is Coming to town

Economic Update

Sharing growth and uncertainty around Policy

By Regions Economic Division

The very mention of December evokes imagery in the minds of many. Some envision family gatherings, blankets of snow, gifts wrapped under a tree, and, for the investors among us, the cheeriest of all seasonality phenomenon – the Santa Claus rally. Recent elections have buoyed investor sentiment, and the S&P 500 is on pace to have its best consecutive two-year calendar performance since 1998 and 1999. However, as we approach the new year, many questions remain about policies under the new administration. Like a child nestled in bed on Christmas Eve – caught between the excitement of the present and the uncertainty of the future – investors are also full of hopeful anticipation shadowed by the unknown.

After reviewing the economic and market environment, Highland and Regions offer the following comments on the current landscape:

Even as job and wage growth slow, growth in labor earnings will continue to outpace inflation, helping support growth in consumer spending, with lower interest rates supporting spending on consumer durable goods. Spending growth is becoming realigned with income growth. The trend rate of job growth is slowing, and the baseline forecast anticipates further deceleration in the months ahead. The labor force participation rate, though rising, is expected to remain below pre-pandemic norms, thus limiting any increase in the unemployment rate over the forecast horizon.

With mortgage rates expected to remain elevated over coming quarters, forecasts for housing market activity have been downgraded. Single-family housing starts and sales of new single-family homes are expected to decline in 2025, and the baseline forecast now anticipates a slower pace of house price appreciation than in earlier vintages. Growth in business investment in equipment/machinery is expected to strengthen over the back half of 2025 into 2026, joining investment in intellectual property products to drive growth in overall business investment. Sustained growth in both components is necessary to support faster growth in labor productivity over time.

Inflation is expected to slow, but we expect core PCE inflation to remain above the Federal Open Market Committee’s 2.0% target rate through 2025. The Institute for Supply Management’s monthly surveys point to continued upward pressure on prices of non-labor inputs in the broad services sector. Renewed disruptions in supply chains and shipping networks and the expansion of tariffs would be sources of additional upward pressure on goods prices. There is, however, a high degree of uncertainty around this forecast given looming changes in fiscal, regulatory, trade, and immigration policies on top of more persistent inflation pressures than had been anticipated.

Now that the Presidential and Congressional elections are behind us, it does not mean that the associated uncertainty is. Although the broad contours have started to form, the specific details on what could be potentially significant changes to fiscal, trade, regulatory, and immigration policy have yet to be revealed. The lack of specific details makes forecasting the path of the U.S. economy an even trickier endeavor than usual in the coming quarters. Two policy areas in which the incoming Trump administration seems likely to seek potentially sweeping changes are immigration and trade. Although there are not yet any specific details to go on, we think it worth offering some general points to keep in mind as you process potential impacts of changes to immigration and trade policy.

We’ve heard some argue that changes to immigration will lead to lower rates of inflation, the premise being that less demand for goods and services will put downward pressure on prices. The problem with arguments based solely on demand is that they ignore the supply side of the economy. Less demand does not mean more supply. Rapid growth in the supply of foreign-born labor has been a primary driver of faster labor supply growth in recent years. As such, to the extent immigration reform acts as a brake on the pace of growth in labor supply and, in turn, employment, it could be that the corresponding hit to supply results in greater upward pressure on prices that would offset any downward pressure stemming from less demand. This is a point apparently lost on those who argue immigration reform will curb the pace of house price appreciation, given the extent to which foreign-born labor is a key source of construction labor.

The reality is that long-running demographic trends have resulted in slowing growth in native-born labor supply, a trait by no means limited to the U.S., meaning that foreign- born labor has become an increasingly important driver of growth in the supply of labor. This, in turn, has facilitated faster growth in the supply of goods and services than would have otherwise been the case. The household survey data presented in the monthly employment reports clearly show the impact of foreign-born labor. Among the various demographic cuts of the household survey data is that between native-born and foreign-born labor market participants. Note that survey respondents are not asked about their immigration status, but regardless, foreign-born participants have accounted for rapidly rising shares of the labor force and household employment over recent years; as of November, foreign-born participants accounted for 19.2% of the U.S. labor force and 19.1% of household employment.

Along the same lines, we think there are some general points to keep in mind as the specific details on trade policy emerge over coming months, specifically, whether or to what extent tariffs will be expanded. One question to consider is what the point of expanded tariffs would be, as expanded tariffs could be intended as: 1) a means of raising revenue to help offset higher spending and/or the costs of extending the 2017 tax cuts or implementing any additional tax cuts; 2) a means of addressing trade practices or other policies perceived to be at odds with U.S. interests; 3) a means of protecting domestic producers from foreign competition deemed to be unfair; or 4) a means of directing manufacturing activity to the U.S.

While a specific tariff on a single foreign nation can be some of those things, it cannot be all of those things, which suggests that we are unlikely to see “blanket” tariffs at a specific rate aimed at every foreign trading partner. In the second case above, it could be that the threat of expanded tariffs is sufficient to bring other nations to the negotiating table. That tariffs were deployed in the first Trump administration should remove any doubt as to whether the threat of expanded tariffs is credible.

In terms of the potential revenue brought by expanded tariffs, it helps to note that, of the roughly $3.1 trillion of goods imported into the U.S. in 2023, 43% came from just three nations: Canada, China, and Mexico. To put that in perspective, you’d have to add up the shares of the next 19 countries on that list to arrive at a combined share of 43%. Note that the share of imports coming from China began to erode rapidly in the wake of tariffs put into place during the first Trump administration. This in part reflects firms who had been importing goods from China diversifying supply chains, and also reflects Chinese firms shifting production and/or assembly of goods to other Asian nations.

We’d expect to see the same reactions in response to expanded tariffs on Chinese-made goods, particularly if tariffs are raised as high as has sometimes been suggested. Think about this in the context of the intent of the tariffs, however, and it points to the difficulty of using tariffs to achieve specific objectives, such as a source of government revenue. This suggests significantly higher tariffs on Chinese goods would be unlikely to raise targeted amounts of revenue, and that tariffs would have to be imposed on a much wider group of countries, and tariff rates would have to be higher to achieve the same revenue objectives.

That U.S. exports are similarly concentrated among the same group of countries could be seen as suggesting the U.S. has little to fear from other nations imposing retaliatory tariffs on U.S.-made goods. Of the roughly $2.0 trillion of exports of U.S. goods in 2023, 41% went to either Canada, China, or Mexico; you’d have to add up the shares of the next 18 countries on that list to get to a similar combined share. That said, if Canada and Mexico were to be subject to significantly higher tariffs on imports into the U.S., as has been suggested, that could easily result in more U.S. firms feeling significantly more pain from Canada and Mexico imposing retaliatory tariffs.

These are just a few illustrations of our broader point, which is that even once details of changes to trade policy come to light, the implications of these changes will be anything but straightforward and are likely to take time to fully play out. This adjustment process will likely be something that sends forecasters back to the drawing board given the number of possible permutations, in both policy changes and the reactions to those changes, that can impact the paths of output, employment, inflation, and interest rates.

Investment Strategy Update

Regions Multi-Asset Solutions & Highland Associates

If history is any guide, U.S. large-cap stocks should have the wind at their sails into year-end as the S&P 500 attempts to close out 2024 with a greater than 30% total return. Liquidity remains ample and supportive of further gains, evidenced by a continued lift in prices of riskier asset classes of late. Shorter-term measures of S&P 500 participation have deteriorated in December, but around two-thirds of S&P 500 constituents still traded above their respective 200- day moving average as of mid-month. Breadth has fallen on the S&P 500 but remains solid. However, we will be watching for further signs that leadership is faltering and narrowing, which could be a sign that a pullback is on the horizon. Bullish sentiment approaching the highest level seen this year is another risk worth watching as a contrarian indicator. However, market participants have few reasons to fight the prevailing uptrend in U.S. large- cap stocks into January, and optimism on unchanged capital gains rates could push profit taking into 2025 or beyond, lessening one headwind for stock prices that can come into play at year-end.

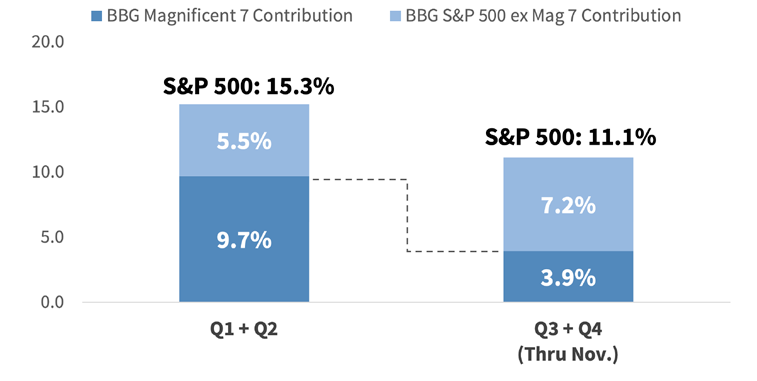

1st & 2nd Half Splits Highlight S&P Leadership Broadening

Source: Bloomberg

The start of December has been an interesting one, as we have seen continued strong performance in some of the Magnificent 7. Year-to-date winners have historically been left out of year-end rallies as investors chase beta. December has been a positive month for equity markets on average, but factor exposures haven’t all fared so well during December, with momentum and quality often generating negative returns over the past decade. Portfolio managers chasing alpha and looking for window dressing at the last minute is reason this may not hold in 2024. Chasing these names could prove to be costly if market sentiment shifts.

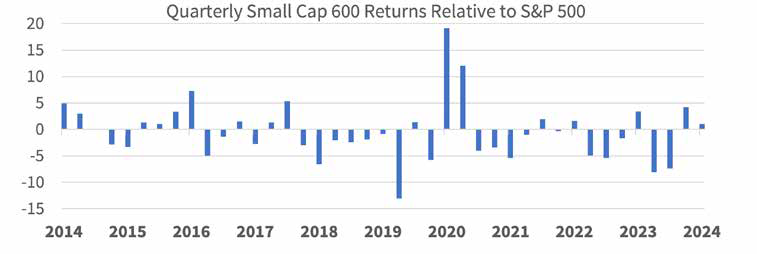

Will a Trump return mean more underperformance for small- and mid-cap stocks? Investors dusted off their 2016 playbook in the wake of the November election, reigniting interest in smaller companies and propelling the S&P Small Cap 600 to a 10.9% gain in November alone, nearly doubling the S&P 500’s monthly return. The small-cap advance rhymed with what occurred in November of 2016, when the small-cap index surged by 12.5%, but companies farther down the market cap spectrum had also led for most of that year up to that point and were in a different fundamental position than they appear to be in today. The potential for a more volatile global trade backdrop in the coming years alone begs the question, does this rotation have staying power, or is it set to fade as it did during President Trump’s first term?

It’s no secret that small- and mid-cap companies rely less heavily on foreign sales to drive profits, and in an environment where U.S. tariffs on imported goods could rise,

The “Trump Bump” Failed to Buoy SMID for Long Last Time

Source: Bloomberg

and with our trade partners potentially responding with tit-for- tat tariffs on U.S. imports, smaller companies should be relative beneficiaries. However, that wasn’t the case after tariffs were implemented in 2017, as the S&P 500 outpaced the S&P Small Cap 600 by 8.6%. Despite the political sparring, the ultimate outcome posed less of a headwind for financial markets and multinationals based in the U.S. than feared. Smaller stocks have attractive valuations relative to their expected earnings growth in the coming year and should provide some insulation in a tail-risk trade scenario if trade/tariff rhetoric ramps up. However, macro tailwinds may not be enough to win over investors and turn them into believers. We are optimistic that an uptick in mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and deregulation will boost smaller stocks in 2025, but it will also provide tailwinds for companies in the S&P 500.

Weakness in the U.S. dollar of late has spurred greater interest in foreign markets, and there is quite a bit of negative news already priced in, particularly for developed markets abroad, evidenced by the MSCI EAFE trading at 14 times trailing 12-months earnings, well below the 30-year average of 20 times. Clarity on the trade/tariff front and some signs of stability in the U.S. dollar could drive improved sentiment surrounding international markets in the coming year, and it might not take much in the way of positive news to do so amid low valuations and paltry expectations for economic growth and earnings abroad. With that said, outlining a path higher for U.S. stocks is a far easier exercise, and we expect the S&P 500 to outpace foreign developed markets in the coming year as capital continues to flow into U.S. assets.

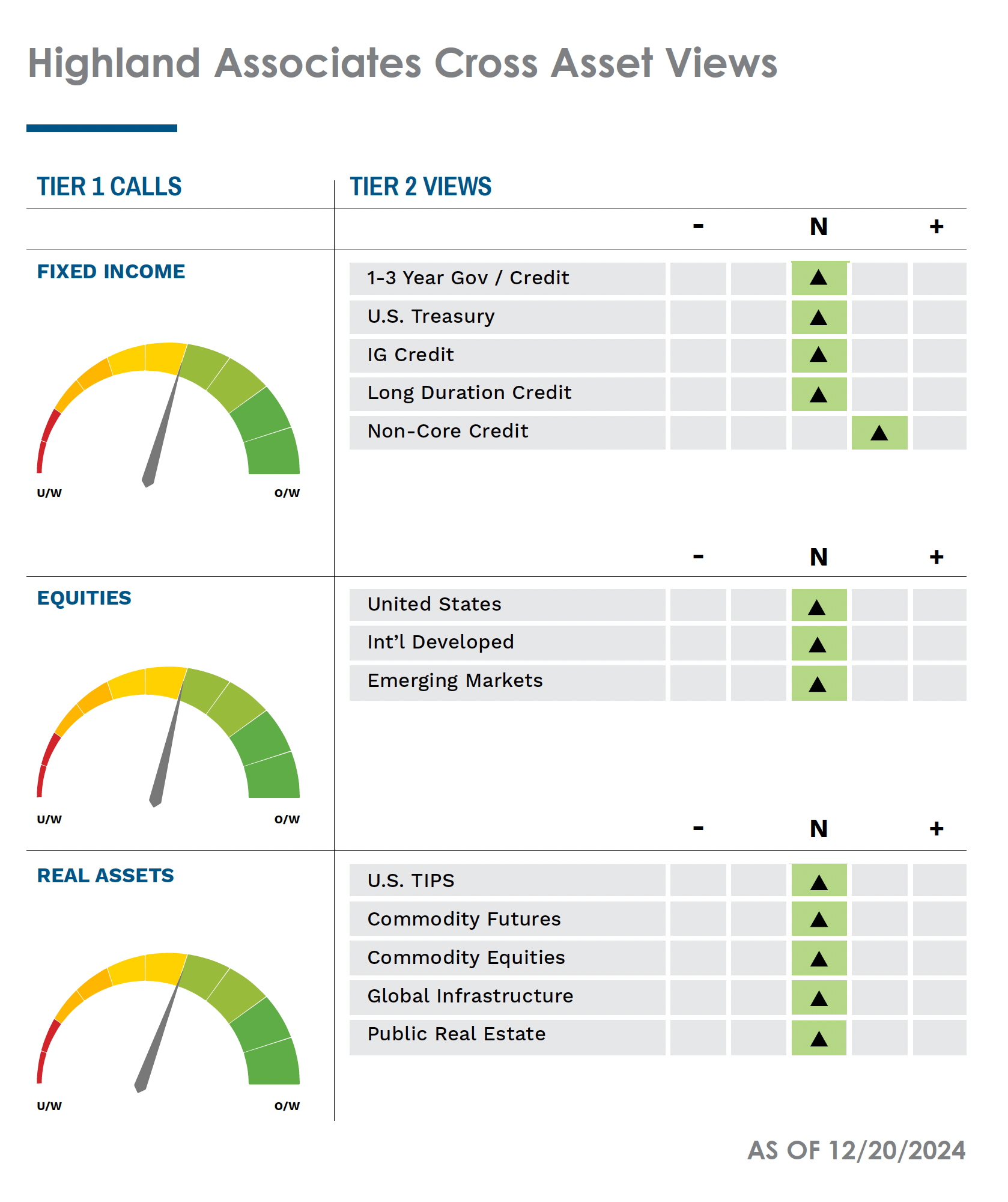

Calm returned to the bond market in the back half of November as President-elect Trump announced that he would tap hedge fund manager Scott Bessent to be Treasury secretary, a move cheered by fixed-income investors that led to a rally in long-dated U.S. Treasuries and forced yields lower. Market participants view Bessent as a student of history and rational thinker equipped with the right stuff to guide the U.S. government through the challenge of making interest payments on some $35T of debt, all while the budget deficit continues to grow with little near-term spending relief on the way. Tough decisions must be made in the coming year(s), and after focusing issuance on the short-end of the Treasury curve via bills in recent years, the U.S. government needs to term-out borrowing by issuing more long-term notes and bonds. To make this pivot without rattling markets and forcing Treasury yields higher, insurance companies, pension plans, and sovereign wealth funds must buy into the idea that the U.S. government can make strides toward getting its fiscal house in order, and Bessent’s nomination has, at least initially, been viewed as doing just that.

While market participants received clarity on who would lead the U.S. Treasury, certainty on the tariff front may remain elusive for a while longer, putting a floor under long-term Treasury yields. Tariffs on Chinese exports are expected to rise but could end up below the 60% rate bandied about when the President-elect was on the campaign trail, and with recent cabinet appointments taking on a less protectionist or nationalistic tone, “blanket” tariffs on all imports appear less likely. Ultimately, cooler heads should prevail, but tariff rhetoric will be used as a negotiating tactic for some time to come and interest rates will likely remain volatile as a result. A more targeted approach to tariffs would ease fears that inflation could spike and in turn lowers the likelihood that the 10-year Treasury yield is on a collision course with the 5% level, or above, over the near term. However, we see little downside for yields on long-term Treasuries as investors require greater compensation for taking on interest rate risk amid this highly volatile and uncertain backdrop. As a result, we view core investment-grade bonds, specifically Treasuries, as a “clip your coupon,” at best, asset class over the balance of 2025. U.S. corporate high yield, floating rate bonds, asset-backed securities, and developed market sovereigns abroad all hold appeal for diversification purposes and help lower the volatility profile of fixed-income portfolios.

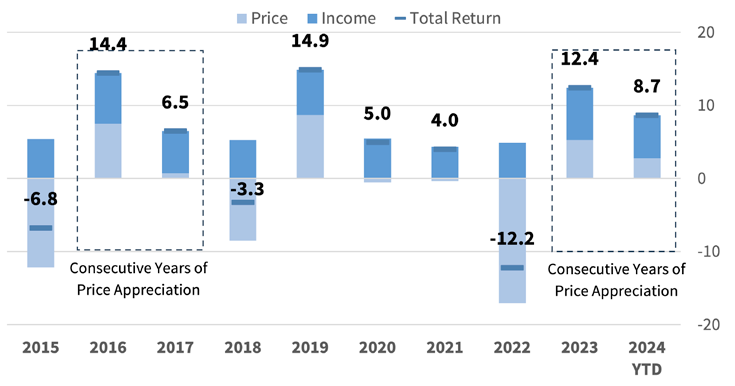

Credit markets may have a little too much cheer heading into the new year. Valuations in below investment grade credit capped off their fourth consecutive month of spread tightening in November, a streak last seen in the second half of 2020. The recent run of spread tightening for high-yield bonds has started to dampen the relative appeal of corporate credit. The Bloomberg High Yield Index has returned a hefty 8.7% with just one month to go in 2024, topping the index’s 7.6% yield-to-worst at the start of the year as the combination of credit spread compression and rate movement have driven prices ever higher. Price appreciation in high-yield land shouldn’t be taken for granted, as it has now only occurred in five of the last ten years with the only other repeat occurrence before the last two years happening in 2016 and 2017.

Those historical statistics alone aren’t enough to drive us out of below investment grade securities, as market “firsts” happen often, but when viewed in concert with ultra-tight corporate credit spreads, the data warrant a deeper dive to ensure one is not taking unnecessary risk in what could be a more volatile market going forward. Valuations are just one factor in forecasting market returns in our approach, but with spreads just 30 basis points above the all-time tight level reached in 2007, investors will likely benefit from taking a more guarded approach to below investment grade corporate bonds in the coming year. Given our current position in the economic and credit cycle, we see few catalysts for a sizable sell-off in high-yield corporates, but we hold the view that investors should be tempering their expectations for this segment after back-to-back years of above-average returns.

If History Holds, Tougher Times May Lie Ahead for High Yield

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; U.S. Census Bureau; International Trade Administration

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES: This publication has been prepared by the staff of Highland Associates, Inc. for distribution to, among others, Highland Associates, Inc. clients. Highland Associates is registered with the United States Security and Exchange Commission under the Investment Advisors Act of 1940. Highland Associates is a wholly owned subsidiary of Regions Bank, which in turn is a wholly owned subsidiary of Regions Financial Corporation. Research services are provided through Multi-Asset Solutions, a department of the Regions Asset Management business group within Regions Bank. The information and material contained herein is provided solely for general information purposes only. To the extent these materials reference Regions Bank data, such materials are not intended to be reflective or indicative of, and should not be relied upon as, the results of operations, financial conditions or performance of Regions Bank. Unless otherwise specifically stated, any views, opinions, analyses, estimates and strategies, as the case may be (“views”), expressed in this content are those of the respective authors and speakers named in those pieces and may differ from those of Regions Bank and/or other Regions Bank employees and affiliates. Views and estimates constitute our judgment as of the date of these materials, are often based on current market conditions, and are subject to change without notice. Any examples used are generic, hypothetical and for illustration purposes only. Any prices/quotes/statistics included have been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but Highland Associates, Inc. does not warrant their completeness or accuracy. This information in no way constitutes research and should not be treated as such. The views expressed herein should not be construed as individual investment advice for any particular person or entity and are not intended as recommendations of particular securities, financial instruments, strategies or banking services for a particular person or entity. The names and marks of other companies or their services or products may be the trademarks of their owners and are used only to identify such companies or their services or products and not to indicate endorsement, sponsorship, or ownership by Regions or Highland Associates. Employees of Highland Associates, Inc., may have positions in securities or their derivatives that may be mentioned in this report. Additionally, Highland’s clients and companies affiliated with Highland Associates may hold positions in the mentioned companies in their portfolios or strategies. This material does not constitute an offer or an invitation by or on behalf of Highland Associates to any person or entity to buy or sell any security or financial instrument or engage in any banking service. Nothing in these materials constitutes investment, legal, accounting or tax advice. Non-deposit products including investments, securities, mutual funds, insurance products, crypto assets and annuities: Are Not FDIC-Insured I Are Not a Deposit I May Go Down in Value I Are Not Bank Guaranteed I Are Not Insured by Any Federal Government Agency I Are Not a Condition of Any Banking Activity.

Neither Regions Bank nor Regions Asset Management (collectively, “Regions”) are registered municipal advisors nor provide advice to municipal entities or obligated persons with respect to municipal financial products or the issuance of municipal securities (including regarding the structure, timing, terms and similar matters concerning municipal financial products or municipal securities issuances) or engage in the solicitation of municipal entities or obligated persons for such services. With respect to this presentation and any other information, materials or communications provided by Regions, (a) Regions is not recommending an action to any municipal entity or obligated person, (b) Regions is not acting as an advisor to any municipal entity or obligated person and does not owe a fiduciary duty pursuant to Section 15B of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 to any municipal entity or obligated person with respect to such presentation, information, materials or communications, (c) Regions is acting for its own interests, and (d) you should discuss this presentation and any such other information, materials or communications with any and all internal and external advisors and experts that you deem appropriate before acting on this presentation or any such other information, materials or communications.

Source: Bloomberg Index Services Limited. BLOOMBERG® is a trademark and service mark of Bloomberg Finance L.P. and its affiliates (collectively “Bloomberg”). BARCLAYS® is a trademark and service mark of Barclays Bank Plc (collectively with its affiliates, “Barclays”), used under license. Bloomberg or Bloomberg’s licensors, including Barclays, own all proprietary rights in the Bloomberg Barclays Indices. Neither Bloomberg nor Barclays approves or endorses this material or guarantees the accuracy or completeness of any information herein, or makes any warranty, express or implied, as to the results to be obtained therefrom and, to the maximum extent allowed by law, neither shall have any liability or responsibility for injury or damages arising in connection therewith.